- Home

- Latifa al-Zayyat

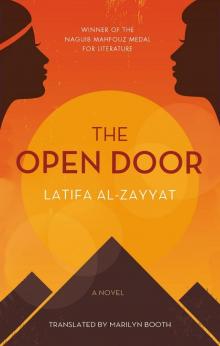

The Open Door Page 3

The Open Door Read online

Page 3

Gamila shook her head slowly, her eyes resting somberly on her cousin. At her mournful look, a sense of dread seemed to fill Layla’s body. She didn’t know where the sensation came from, and uncomfortably she started forward, meaning to throw her arms around Gamila. But she stopped dead when she caught sight of Adila’s mocking, superior gaze.

“Congratulations, Madame Layla,” said Adila with a smile of scorn. “You’ve grown up now.”

Gamila gently drew Layla away. In the school bathroom she cut away the red spot with a razor. When Layla’s mother saw the pinafore she exclaimed, “My dear! Why didn’t you wash the spot out instead of cutting your pinafore?” But this time she did not treat Layla roughly at all.

Layla shifted her body warily in her bed, stretching slowly as if she were made of fragile glass that might shatter at a touch. She lay on her back, her eyes staring into the darkness. How strange this all was! She had only sensed the curious heaviness in her body when she had seen that look in Gamila’s eyes. And it was the same expression she’d caught in her mother’s gaze. What had happened, of course, had happened long before Adila’s discovery of it, maybe even while she had sat in class that morning, but still, she had not felt the slightest bit sick or tired this morning. To the contrary, she’d felt light in mind and body, she had been ready to run and laugh and bury her face in the blooms of the garden. She’d felt strong, and smart, and as if she could get ahead of Nafisa in arithmetic. But now, Layla realized suddenly, her eyes still wide open in the darkened room, it all seemed totally insignificant. Everything did—Miss Nawal, Nafisa, arithmetic. It seemed as if all of those events had happened to her a long time ago. She closed her eyes and tried to summon the image of Miss Nawal bending over her desk. She concentrated so hard on that image that she felt sweat breaking out on her forehead. Yet the picture remained faint, fleeting, out of focus; and it was quickly erased by the scene at the sycamore tree, and Gamila, giving her a look that reflected a sorrowful, loving sympathy.

“But why, Gamila, why?” Layla found herself saying out loud. “I want to get older. Yes, I do.” Her eyes open again, she stared into the blackness.

To grow older. To become like her mother. No! To become like . . . like the history supervisor who helped their teachers, the woman with the broad, pale forehead, who held her head so erect, with her long, carefully coiffed black hair, and her gait as measured and dignified as that of any queen.

Layla heard the front door open. The light on in the front hall seeped into her bedroom, and to the bed where she lay; and then it disappeared as her father headed for his room, which shared a wall with hers. When she had arrived home from school that afternoon, he had already gone out. At the table her mother told her that he had been invited to dine out.

Now her father would learn of it. He would certainly find out, for her mother would tell him. What would he say, she wondered? He would be happy, of course, and he would show it, as he had when Mahmud’s chin had first sprouted a beard.

On that day, she recalled, her father had stopped Mahmud and had drawn him over to the window where the light was stronger. He had stared at his son, and the look in his eyes had made Layla wonder whether he still had his feet on the ground! He seemed to be soaring somewhere above, Mahmud in tow. His face had reddened; he had laughed and laughed, for no reason at all.

The laughs died away . . . the stillness grew to encompass everything, and Layla’s eyes stared into the darkness, as if in wait. Now she could hear her mother’s voice, lowered; she stiffened as she made out her own name, and heard it come up again and again in the conversation. Then silence hung thickly over the room once again, an absolute stillness, a massed darkness.

A sobbing wail sliced through the silence and Layla jumped out of bed as if stung. But immediately she recognized her father’s tones in that wail. She stood transfixed in the middle of the room. She heard pleading invocations to God cut into the sobbing—“Lord, give me strength! She’s just a helpless girl. Oh God!”—interrupted from time to time by her mother’s voice, calm and low.

“That’s enough, ya sidi! The girl can hear us.”

“Protect us, Lord, protect us! Shield us from harm.” The voice grew fainter until, with a final choked sob, it was silent. Layla felt a desolate emptiness expand to fill her chest, and a tremor that began on her lips moved to her hands and legs. Sweat trickled from the nape of her neck all the way down her back. Moving about in the darkness, groping for the door, she struck against something and wanted to scream, to call out to her mother. “Don’t be afraid, dear,” her mother had said that afternoon; now, the scream faded on her lips. Her legs felt heavy; she dragged herself back to the bed and lay down on her back. “Don’t be afraid, dear, don’t worry. You’ve grown up.” And Layla tugged at the coverlet, yanking it over her body, over her face, pulling it up to the very top of her head.

On that remarkable evening Layla had not been able to fathom why Gamila had given her that melancholy gaze, or why her father had wept. It was only with the passage of years that she came to understand—and then she understood very well, indeed. She grew to the realization that to reach womanhood was to enter a prison where the confines of one’s life were clearly and decisively fixed. At its door stood her father, her brother, and her mother. Prison life, she discovered, is painful for both the warden and the woman he imprisons. The warden cannot sleep at night, fearful that the prisoner will fly, anxious lest that prisoner escape the confines. Those prison limits are marked by trenches, deeply dredged by ordinary folk, by all of them; by people who heed the limits and have made themselves sentries. Yet the prisoner feels in her bones that she is strong, that she has powers within her, ones she has never before sensed; she knows the abrupt and shocking strength of a body developing, growing. She finds herself held by powers that sweep all before them, that impel her toward freedom. She sees forces in her body that those border trenches work to enclose and contain; and she knows powers in her mind that the confines themselves work to impound. For they are insensible limits that neither hear, nor see, nor perceive. Layla’s father had outlined those confines as the family sat around the table, eating lunch. His voice showed no uncertainty or hesitation.

“Layla, you must realize that you have grown up. From now on you are absolutely not to go out by yourself. No visits. Straight home from school.”

Turning his eyes on Mahmud, he added, “I don’t want to see any novels or girlie magazines around here. Understand?”

Mahmud dropped his head and twisted his lower lip. His father’s voice grew less harsh. “If there’s something you want to read, you can read it outside the house. Don’t try to bring it here and hide it. I don’t want anything poisoning the girl’s mind.” His eyes met Mahmud’s, a man-to-man gaze, and son gave father a knowing smile.

“And, Mahmud, I don’t see any reason why your friends need to visit you at home. Aren’t the cafe and the club enough, pal?”

Mahmud’s smile broadened. “Yes, Papa, they are. But what about Isam? He studies with me.”

Her mother’s eyes traveled upward from her plate, clouded with worry. “Isam—now really, is he a stranger? He’s your cousin, my sister’s son! Layla’s not going to cover herself up in front of her cousin.”

Their father wiped his mouth with his napkin. “Isam, well, never mind that. Isam is one of us.”

Layla said nothing. No one expected any words from her. Now it was her mother’s turn—her mother’s turn to play a never-ending role. And she performed it so assiduously that now, whenever Layla heard steps, she would automatically throw a glance behind her, in expectation of her mother’s harsh words of blame for whatever it was she had most recently done, whatever error she had supposedly committed or problem she had caused. The worst of it was that she never knew what it might turn out to be. Something “improper,” something “inappropriate,” something that did not befit the daughter of respectable folk. A sudden laugh, straight from the heart, was “improper.” Why? Too loud. Any stateme

nt that Layla thought frank and sincere was labeled “out of bounds.” Out of what bounds? The bounds of polite conduct. “There’s something, dear, called the fundamentals—the rules, the right way to behave.”

And then there was the matter of sitting. “Goodness, Layla! Either you sprawl across the chair like a know-it-all or you swing one leg across the other—what will people say? I can already hear them grumbling—‘She wasn’t brought up right.’”

“People, people. I’m sick of people. I don’t want to see anyone.”

“Stop it! People must see you, of course. Otherwise, they’d say, ‘Why’s she hidden away? Is her arm crippled, or what? Or is she lame?’”

If she refrained from going into the living room to greet guests, her mother accused her of being “a recluse—you don’t like anyone.” But if, on the other hand, she did go in to greet them, her mother scolded her for not conversing animatedly. Yet if she spoke up, her mother said she was interfering in adults’ business. If she stayed, sitting in silent politeness, her mother waved her out of the room! But whenever she tried to make a hasty retreat, her mother would say, “Why were you in such a rush?”

“Mama, I don’t know what to do! You’ve completely confused me now. Everything I do turns out to be wrong, wrong, wrong!”

“Whoever lives by the fundamentals can’t possibly go wrong.”

“So what are these fundamentals?”

“The fundamentals are when one . . . ” And so her mother would set new limits, add new restrictions. They were like water dripping rhythmically onto a sleeping person, the regularity of them stealing the sleep from her eyes, drop by drop, hour after hour, day by day, year after year.

And year after year, Layla grew.

Chapter Two

AT SEVENTEEN LAYLA HAD FILLED out into a bronze-skinned, moderately tall young woman. Her face was pleasantly round, her features fine and regular under a wide brow. Her eyes were a rich hazel, deep and tapered with an intense sparkle, narrowing to shimmering slits when her rosy cheeks lifted in a smile. She could break into confident laughter that absorbed her entire face, transforming her lips, eyes, and even her nose. When a conversation sparked her interest she would tilt her head, immersed as the words tumbled from her ears straight into her heart; and if someone said something that aroused her enthusiasm or compassion her eyes would glisten with sudden tears. Her face radiated movement, liveliness, and a luminous glow.

And that glowing face shone in utter contrast to her body. For she walked as if bound in heavy chains, dragging her body behind her, shoulders hunched and head pitched forward as if determined to get where she was going with the utmost haste before she could possibly attract the glances of others. If she sat down she found it almost impossible to settle in any position. She never knew where to put her hands; they seemed bodies apart, foreign to her. Her movements spoke of heaviness and fear, especially at home; at school she moved more freely. For school was part of the world she loved with its echoing chorus of varied sounds: the bell; ringing laughter, and sometimes suppressed chuckles; steps sounding through the corridor hurrying to class; eyes that spoke in smiles, and loud mirth in the classroom. Then there were the whispered conspiracies drummed up against the teacher; the loyalty that bound the girls together and neither threat nor punishment would fracture; the notes passed around when speech was out of the question; the midday break and the clusters of friends drawn to each other. That world included, too, murmured jokes that elicited blushing cheeks first, and only then peals of laughter; stories told in undertones in remote crannies of the school grounds, leaving listeners with their mouths stupidly agape; the rhythm of spoons against plates in the cafeteria; the endless banana sandwiches and insult sessions, and the times they had locked themselves into a classroom at break time to dance. Political discussions, disagreements over the merits of Umm Kulthum’s singing as opposed to the crooning of Abd al-Wahhab, friendships that flowered and faded just as suddenly, the break-ups and tears and peace-making. Layla was capable of drawing the entire class’s attention with her practiced naughtiness, angering the teacher, then making amends, making impromptu speeches on nationalist occasions and distinguishing herself in school literary clubs. The Arabic teacher acknowledged her superiority; she could be school champion at ping pong. She was an energetic Girl Scout, a team player at basketball and leader of a gang of girls wallowing in mutual adoration. But at the end of the school day, after the last pupil had departed, the school silent and empty, she would go into her classroom, gather her books, and leave for home with dragging steps.

No sooner was she home than her mother started nagging, her voice and manner rough. There was always some little thing. Either it was something that should have been done and had been neglected, or it was something that should never have happened but had. Then her father’s taciturn, expressionless demeanor would appear, to impose his deathly stillness on everyone in the apartment. Her mother’s walk would become a hushed tiptoe as she turned this way and that, peering everywhere with anxious eyes to reassure herself that all was properly prepared; then

the main, midday meal would begin. Sitting at table, her father would find something with which to rebuke her mother, quietly, of course, his voice hardly above a whisper. Naturally, her mother was vigilant not to commit any act that might draw censure. But there were her siblings; and of course she had to bear full responsibility for their conduct. Her brother had said such-and-such, and it shouldn’t have been said; he had done this or that when he should have known better. Her mother never responded, but her tightly pressed lips would

grow white.

Lunch was a far happier affair when Mahmud was not tied up at the College of Medicine; when, instead, he would come home at the end of a long morning and pull a chair up to the table, letting them enjoy his amiable, bright face, as his restless, green eyes roved around the room. With a pretence at seriousness in his voice, his delicate, pale lips would launch into the day’s events. “Well, today . . . ,” and he would go on to tell them everything—what transpired at the college, the exchange he had overheard in the tram, the latest book he had read, the newest joke going around. He imitated people, offered commentaries, exaggerated, and asserted as evidence opinions that were odd indeed, views that set him apart from others. The atmosphere at the midday meal would shift completely, as if his entrance had brought a fresh breeze from outside into the Sulayman home. His mother’s taut, worried features relaxed, her face now that of a sweet child as she laughed in that gentle, quick, understated way she had. But the sight really worth seeing was their father’s face. Eyes trained on Mahmud, never lifting off his face, as if the young medical student was a miracle moving across the face of the earth, the father would sit motionless, listening raptly, the mask falling gradually from his face; that dour mien, normally empty of expression, would take on a bearing of affectionate concern. And at the point when Mahmud’s dramatic narrative displayed his own superiority or courage or cleverness or humor, the father’s gaze would lightly layer with tears.

Then Mahmud would start on his mocking criticisms of the social conditions and niceties that reigned his society. He was merciless; of those many traditions ringed in haloes of sanctity, there was not a single practice that his devastating attacks skirted. Layla’s eyes glowed, her mother’s lips trembled, and the father’s face always darkened, suspecting a danger he could not define. But Mahmud would slip adroitly out of the dilemma he had created, mixing just enough humor into his sarcastic flings to keep his father busy with the hopeless attempt to suppress his laughter, uncertain of whether his son was serious or merely pulling his leg.

Conversation flew every which way, but mostly it settled back into politics, especially when Isam joined them for lunch. And more often than not he did, for he and Mahmud were inseparable, always together at the College of Medicine, always together when they studied. Whenever talk turned to politics Layla craned forward over the table, leveling her eyes at Mahmud, her ears trained on whatever Isam

and her father said but her gaze never leaving her brother. Now and then the muscles in her face twitched as if she had a response at the ready, a stinging riposte; her mouth would move, silently forming letters, but then her face would ease into a smile as Mahmud answered, for invariably he said exactly what she had wanted to express.

“Gamila, do you know what Papa says?” she commented one day to her cousin. “He says that Mahmud and I think with our hearts, not with our minds.”

“He’s kidding you, silly.”

“Well, I know, but anyway, it’s the truth.”

When Mahmud straightened his spine, it signalled that serious discussion was about to begin. As he spoke, he looked hard at Isam, as if his friend and cousin were responsible for everything the government did.

“So can you tell me what this Wafdist government of yours has done now? ‘The Wafd,’ we insisted, over and over. ‘Only the Wafd can save the country.’ So then, what has the Wafd actually done?”

“It’s a question of time,” Isam protested. “The world wasn’t created in a single day, you know.”

“Don’t drive me up the wall, Isam. You know perfectly well that the negotiations won’t lead to anything. The whole country knows it, too. And it isn’t as if everyone has just woken up to the fact—we’ve all known it for years.”

Wiping his mouth, their father would join the conversation. “In any case, the Wafd is the best of the lot.”

Mahmud leaned forward, the words storming from his mouth as if he were picking a quarrel. “The Wafd is the lousiest of the lot, because the people trusted the Wafd, and then it went and betrayed their trust.”

Their father would hurry off to the bathroom without answering, for he must do his ablutions swiftly so that he would not be late for the afternoon prayer.

The Open Door

The Open Door