- Home

- Latifa al-Zayyat

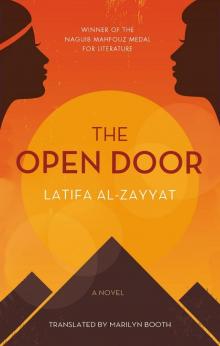

The Open Door

The Open Door Read online

Latifa al-Zayyat (1923–96) struggled all her life to uphold just causes—national integrity, the welfare of the poor, human rights, freedom of expression, and the rejection of all forms of imperialist hegemony. As a professor of English literature at Ain Shams University, her critical output was no less prolific than her creative writing, but the creative, academic, and political strands of her personality were interwoven.

The Open Door is generally recognized as al-Zayyat’s magnum opus and was awarded the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 1996.

Marilyn Booth has translated works by Hoda Barakat, Nawal El Saadawi, Hassan Daoud, and many other Arab writers. She is Khalid bin Abdullah Al Saud Professor in the Study of the Contemporary Arab World in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University.

The Open Door

Latifa al-Zayyat

Translated by

Marilyn Booth

This edition published in 2017 by

Hoopoe

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.hoopoefiction.com

Hoopoe is an imprint of the American University in Cairo Press

www.aucpress.com

Copyright © 1960 by the Estate of Latifa al-Zayyat

First published in Arabic in 1960 as al-Bab al-maftuf

Protected under the Berne Convention

English translation copyright © 2017 by Robin Moger

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 821 5

eISBN 978 1 61797 153 2

Version 1

To my teacher, Rashad Rushdi

Chapter One

FEBRUARY 21, 1946. SEVEN O’CLOCK in the evening: the tranquil sky bore a pleasant coolness, and there was a clean purity to the air as if the heavens had poured down rain and washed the earth. Yet Cairo was not its normal, brightly lit self; its main streets were not choked with the usual crowds streaming through the cinema houses, shops, and cafes, or congregating at bus and tramway stops. The cinema houses were on strike, and so were other businesses, and no buses or trams were running. Police cars and vans slunk along streets packed with rifle-bearing soldiers. The few civilians in sight walked slowly in the streets or stood at intersections, knots of two, three, or four engaged in conversation. One could hear all sorts of dialects and levels of education in their speech, but every exchange turned upon the same subject, that morning’s events in Ismailiya Square.

“That clash was no coincidence, no sir! They meant to provoke people. A demonstration of forty thousand folks, a big show of protest against the English, that’s what people came out for—and what happens? Those English bring out five armored cars to plow into it!”

“Don’t forget we Egyptians are brave—a country of tough guys. The tank crushed the lad and right away the students raised his shirt high to show everyone; there was blood all over it. Then the crowd just went mad. They attacked the English tanks and pulled ’em apart, and then they started throwing their bodies right on the guns—why, you’d have thought they were made of sugar for all the people swarming around them.”

“Now, personally, I consider this demonstration a new stage in our national struggle. First: this was a direct clash with the English. Second: the army refused to break up the demonstration. Not only that—our army vehicles were moving through the city plastered with nationalist slogans!”

“Then there’s the way the workers joined the students. And everybody—all the Egyptian people.”

“I’m telling you, this is a nation of toughies—even the women came out of their houses. There were women all over the place in Bab al-Sha‘riya.”

“Let’s get to the point—and that’s the weapons. The bullets were coming thick and fast from the army posts. The people were unarmed. If only they had had guns!”

“Fine, but did you see all of those bricks, raining down on the English? Brother, I couldn’t believe it! Where’d folks come up with so many bricks?”

“Yes, and how about when they set fire to those barricades the English were trying to hide themselves behind?”

“Those boys were ripping off their gallabiyas, soaking them in gas, and setting fire to them. They were totally in flames, might eat up a guy’s whole body, but what did they care? They would just crawl along, bullets pouring down like rain, paying no attention, no sir, went on moving, right to the attack . . . .”

“This wasn’t simply an anti-English thing today. No, people were attacking the English and the king, and agents of imperialism in general. And I say this is a new stage of national consciousness, that’s my own personal view of the situation.”

“Well, me—even if I live to be a hundred I won’t ever forget that scene in Sulayman Pasha Street. No, sir.”

“Badges, badges of blood! The blood of those who died, those who were wounded, all for Egypt’s sake. Twenty-three dead, and 122 injured.”

*

For those talking excitedly on the street the battle had ended. Final gains and losses had been tallied. But the battle had not yet ended, nor had any sums been figured, for the family of Muhammad Effendi Sulayman, civil servant in the Ministry of Finance and resident of No.3 Ya‘qub Street in the neighborhood of Sayyida Zaynab.

In the apartment’s large entrance hall, which served the family as an everyday living room, sat Sulayman Effendi himself. Ensconced in a cushioned wooden armchair facing the front door, he was repeating verses from the Qur’an in an undertone, stopping from time to time to listen hard whenever footsteps sounded on the stairs. As they came closer he would train his gray eyes on the door, his face set severely. But invariably the footsteps continued on, right past the door, up the stairs to the floors above. At that, his shoulders would slump and his sallow complexion would go even paler, giving more prominence to the patches of reddened skin on his face. Eventually he would resume his murmured repetition of verses from the Holy Book.

In the formal sitting room that adjoined the front hall, Sulayman Effendi’s wife stood at the window. She was not a tall woman, but her full figure and light skin were attractive. At the moment the upper half of that compact body hung so far out of the window that she seemed almost to dangle. All her fiber was telescoped into her small, hazel eyes, flitting right and left, staring into the distance as if they could almost of their own accord pierce the dimness of the evening street.

In front of the round table that graced the center of the sitting room stood eleven-year-old Layla, a robust girl with skin darker than her mother’s. She was fiddling with a wooden cigarette box, her motions mechanical, her bright eyes gazing into the distance, at nothing in particular. With a final, sharp tap to the lid of the cigarette box, she marched into the living room, passing her seated father as she headed straight for the front door. She reached for the sliding bolt. Her father’s lips trembled, his face going even whiter as he raised eyes so faded they might have been gazing from a corpse rather than from Sulayman Effendi. He stared at his daughter.

“Where’re you going?” he asked in low, edgy tones.

“To look for Mahmud.” At her words and the hint of defiance in her voice, his dreary eyes flashed. He closed them. “Get back inside.” He reinforced his words with a fling of his hand, as if sensing the weary incapacity his broken voice conveyed.

Layla went over to him. Pausing by his chair, she searched for words that would not come. She put out her hand, meaning to lay it gently on his shoulder, but halfway there it hung motionless in mid-air and then dropped heavily to her side. Tears curtaining her

eyes, she scurried to her mother in the next room and seized her arm.

“Mama . . . Mama!”

At her touch and her whisper the figure at the window gave a little jump, as if grazed by an electric current, and whirled round, a startled fear contouring her face.

“What is it?”

“Don’t be afraid, Mama. Don’t worry, I know Mahmud is fine. He’ll come now, he must, he’ll come. This morning . . . ” But her tears choked off the rest of her sentence.

Her father fidgeted in his chair. That morning—just that morning—he had urged his son, “Don’t go out, Mahmud.” Already at the front door, the lad had paused.

“Nothing to worry about, Papa. It’s to be a peaceful demonstration.”

“So the demonstration can’t go on without you?”

Mahmud had laughed. “Sure, Papa—but look, if everyone said that, then it really wouldn’t go on.”

“You’re still a child. When you start at the university, then you can do what you like.”

“I’m not so little. I’m in my fourth year of high school, and I am exactly seventeen years old.”

Now, hours later, Mahmud’s father bit his lower lip until it stung. If only he had given the boy a good thrashing and then had locked him in—if he had just thrown him into a room and taken the key from the lock—then at least he would know his son’s whereabouts. But if he were to inform the police at this point, no doubt they would arrest him, and if they arrested him . . . . It was Sidqi. Sidqi Pasha, who buried people alive. But what could he do? The boy might be hurt, wounded. He might be . . . . “Spite the Devil,” he muttered to himself.

The clock on the wall above him began to sound the hour. Hardly breathing, Mahmud’s mother listened and counted: seven chimes. She faltered for a moment, hung back, then rushed into the front room and planted herself before her husband, fixing him with frightened eyes that swung sharply from side to side.

“The boy is gone! He’s gone for good! Gone!” She struck one palm against the other in a gesture of futility, seemingly unaware of the noise she was creating. Her normally soft, slightly limp features abruptly acquired an unfamiliar hardness. “If you won’t go out—” The words died on her lips as her flustered husband struggled to his feet. On the stairs the sound of footsteps grew louder, the footfalls of more than one person, heavy and slow, steps that dragged. Layla ran to the door, her father close behind, and burst onto the landing with a shout.

“Mahmud!”

Still inside, her mother reeled and would have fallen had her fingertips not clutched the edge of the chair just in time. But when Mahmud came in, leaning on Isam’s shoulder, she collapsed onto the floor in a faint.

The next morning Layla asked to see her brother before leaving for school. Her mother, eyes red and swollen, gave her a peculiar look as if she held a secret she was unwilling to share. Mahmud was still sleeping, she told her daughter in a whisper. Layla was uneasy, wondering what her mother’s expression and manner of speaking meant.

“What’s happened, Mama?”

As her mother leaned over, her swollen eyes took on a hard glint, the resistant fear of one who senses that she is the target of a well-aimed pistol. She spoke in the same whispered tone. “A bullet. A bullet went into his thigh.”

“I already know that, Mama.”

Her father broke in, lather covering his face. “Really, now—you like to make everything sound so terrible. I told you the doctor said it was a simple wound, no more than a scratch.”

His wife waved his words away and began to count the day’s household chores on her fingers, that strange, secretive look still masking her eyes. Layla gave her shoulders a dismissive shake and stood by the front door to await her cousin Gamila, her mother’s sister’s daughter who lived on the seventh floor. The moment she spied Gamila’s hand through the door’s glass panel, reaching across to ring the doorbell, Layla flung the door open. She closed it behind her slowly and very, very carefully.

It was not until they were on their way down the stairs that Gamila spoke. “What’s wrong, Layla?”

“Nothing.”

“No, I don’t believe you. On the Prophet’s honor, is there really nothing wrong?”

They came out into the street and turned in the direction of their school. “Yesterday was quite a day!” said Layla.

“Why? Did something happen?”

“Isam didn’t say anything?” Layla struck her palm against her chest to dramatize her words.

“Say anything about what?” Gamila asked uncomfortably.

Layla rolled her eyes as she whispered. “About what happened to Mahmud, my brother Mahmud.”

Gamila stopped, her discomfort and anxiety getting the better of her. “What? What’s wrong with Mahmud?”

Layla’s eyes hardened and froze as if she had just espied a gun barrel trained at her skull. She leaned close to Gamila, her words coming out in a measured, loud whisper.

“A bullet . . . a bullet in his thigh.”

Gamila’s schoolbag fell from her hand. Layla gave her a stare and walked on. Gamila ran to catch up, her breath coming in short gasps. “A bullet! Where on earth did this bullet come from, anyway?”

Layla’s head jerked upward. “The English got him. They hit him because he is a nationalist. Because he is a hero.”

“They hit him? Where?”

“Gamila, you never know what’s going on! In the demonstration, of course, the one yesterday in Ismailiya Square.”

“And what did the doctor say? Mightn’t it be just a scratch?”

They were in front of the school. Layla did mean to tell her cousin what the doctor had said and what her father had echoed so firmly, but she saw the look of alarm in Gamila’s eyes and noticed the awed respect, too. She couldn’t help herself as they went inside. “What can he say? It was a bullet, after all.”

A bullet. Mahmud a nationalist. A demonstration. The news caught fire through the school, and Layla found herself—a mere first-year student at the secondary school—the center of attention and admiration. It went on all day long. Older girls swarmed around her and teachers stopped her in the corridors to ask questions. The intensity of their interest intoxicated her, and she let her imagination go. His name? Mahmud Sulayman. His age? Seventeen. Layla, why didn’t he go to the hospital? How could he go to the hospital, they would have arrested him there! So what did he do, then? Well, after he’d been wounded he just went on pelting the English back, the blood was absolutely pouring out but he didn’t stop, his friend kept repeating “enough, stop” but it was no use. His buddy stayed right behind him all the way home, yes, dragged him home to the Astra Building, and they brought in a doctor, a relative, so that no one would find out, and he stayed in hiding as long as it was light, because if he had gone out in broad daylight wounded like that—well what a disaster it could have been!

By the end of the school day Mahmud had become a legend throughout the school building. It was he who had set fire to the jeeps, and to the barricades behind which the English were hiding. It was he . . . and then it was he . . . Layla was sorry to see the school day end.

At the school entrance Inayat stopped her, tugging at her black leather belt to tighten it further around her small waist as the ringlets jostled each other across her forehead. Layla blushed. There was not a girl in her class who did not long for Inayat’s attention. Moving the tip of her high-heeled shoe around in the sand, Inayat said, “Your brother Mahmud—what does he look like, Layla?”

A look of bewilderment crossed Layla’s face.

“I mean, is he dark, light? Tall, short?”

“He’s not dark and he’s not light, he isn’t tall, but he isn’t short, either.”

Inayat laughed and tilted her head pertly so that it almost met her shoulder. “Lovely!” Layla blushed harder but she managed to raise her eyes to the other girl provokingly, with a grin. “Zayy al-qamar, he’s as gorgeous as a full moon.” She could prove the truth of her words, she realized. She took off t

he pendant that hung on a chain around her neck and showed Inayat Mahmud’s portrait in the little cameo. Inayat studied the tiny photograph carefully, and pursed her lips and said grudgingly, “Not bad. Pretty good-looking, in fact.”

Layla took back the necklace and hung it around her neck, staring at the ground. Then she raised her head sharply. “I’ll tell Mahmud that—I’ll say, ‘Inayat says you’re good-looking.’”

“So how would Mahmud know who I am, anyway?”

“All the students at Khedive Ismail know you, in fact they say you’re the reigning beauty queen of the Saniya School.”

Inayat laughed agreeably and pinched Layla’s cheek. “Careful, Layla—watch out I don’t get mad at you.”

Layla stamped her foot on the ground. “I’ll say it. I will. I’ll tell him.”

She took off running in the direction of home. The moment she arrived, she burst into Mahmud’s room, calling his name.

*

But she stopped, suddenly aware of tension in the air. Mahmud was lying on his side, facing the wall, his eyes wide and unmoving as if he had not budged since yesterday. Isam, her aunt’s son, sat on the edge of the bed rubbing his chin, and her mother stood next to him, a glass of lemonade in her hand.

“Come on, son. Sit up and wet your lips.”

There was no sign that Mahmud had heard a word. His mother stepped over to a nearby table and set down the lemonade. She bent over the bed and reached out to feel his forehead.

“What’s wrong, my boy? Tell me—I want to know that you’re all right. What’s the matter—where does it hurt? What are you feeling?”

Mahmud’s face clouded and he spoke without turning to them. “Nothing.”

“What do you mean, nothing?” His mother turned to Isam. “How do you like this state of affairs, Isam? From the minute he got home he’s been like this, he won’t say a word, just lies here moping in this black mood of his.”

The Open Door

The Open Door