- Home

- Latifa al-Zayyat

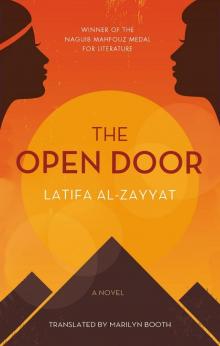

The Open Door Page 23

The Open Door Read online

Page 23

“For what?”

“For everything, all the things he has done. Write that.”

In the end, Layla dictated the letter to Adila. The tears stood in her eyes as she said, “I thank you from the bottom of my heart for what you have done for me. For everything you have done.” This turn of phrase did not please Adila, but she was afraid to protest. She was aware that the slightest opposition might cause Layla to reverse her decision, to cancel the whole idea of the letter once and for all. So Adila thanked Husayn.

When Layla reached the street she sighed with relief, as if she had just left a battle that had exhausted her forces. She felt like someone who had finally faced a long-awaited disaster and realized that the worst was over.

Chapter Sixteen

DR. RAMZI’S CAMPAIGN TO DISTRESS Layla continued in class and outside the lecture hall as well. He pressed so hard that, alone with her friends, she would cry out in desperation, “What does that man want from me? That’s all I want to know—what does he want from me?”

As each term ended she hoped from her heart that she would not be re-assigned to his classes, but her hope was continually dashed. He taught her regularly through her years at the university. If it was not one subject, it was another. She felt as if he were drinking her blood drop by drop, in anticipation of the moment in which it would have all dried up.

He began by focusing his attention on her in class; he seemed to direct all of the difficult questions to her as if there were no other students in the lecture hall. Lobbing a question at her, he would stand waiting, ready to discredit whatever answer she gave; waiting, his distinguished, pallid face empty of expression, speaking to her but as if he were addressing anyone but her, listening to her as if he were paying no attention, his very presence oppressive, constricting every breath she took, but as if he were not really there, as if he stood alone in a glass case that set him apart in grand isolation.

So she would answer; and invariably he would disparage her response. It was not this that angered her, though, for most of the time he belittled whatever any student said. But what did infuriate her was the impression he gave of taking especial pleasure in

ridiculing her responses. Launching into his mockery, a sardonic smile would gleam on his thin, pale lips, and those cold eyes would flash with victory as if he had just aimed a wholly accurate and vicious blow at his worst enemy. He would push aside the glass case and the students would feel that life was beginning to pulse within their professor; a spark would be triggered between teacher and students. Laughter, comments—the god would suddenly turn into a human being who actually made jokes—at Layla’s expense, of course. “No, you still don’t get it. You’re philosophizing, but philosophy isn’t a pot of stew on the stove, Miss.” “Do you know what it is you need? You need brakes—brakes on your imagination. Philosophy is not a figment of the imagination. Philosophy is principles, firm principles; and rules, strict and fundamental rules.” “The philosophy department is not where you belong. You should have gone to one of the literature departments. Maybe your imagination would have served you well there.”

So a silent struggle began, imbuing Layla with its outlines, a struggle she felt compromised her very existence and sucked the blood from her veins. If she did not comprehend at first what Dr. Ramzi wanted from her, it was not long before she understood perfectly. His attitude to life diverged from hers in sharply defined ways. The source of that was not difficult to locate: his whole nature differed from hers. So, she realized, he wanted to humiliate her—precisely her—and to bend her to his will; he must hear her parrot his opinions. The only view he could brook was his own. Indeed, no response one might offer could please him; to be more accurate, he could not regard any answer with pleasure, for as far as he was concerned, pleasure was a vulgar emotion wholly inappropriate to the intellectual, who must at all times impose on his feelings an ironclad structure of thought. No, he could not consent to any answer unless it conformed to his own personal opinion—unless his merchandise was returned to him in full!

This was not a phase of her life in which Layla felt any particular need to assert her will. She resigned herself to a great deal, and tended to yield without argument; but in this case, something led her to put up with the disparagement, the commentaries, and the jokes without crumbling. It almost seemed as if she did not dare to capitulate, for if she had, a danger she could ill define awaited her.

“Just say what he wants to hear and be done with it,” Adila would say.

“He wants me to be a parrot.”

“Parrot, parrot, isn’t that better than having him always picking on you? What’s the big deal about making him happy, hmm?”

Layla had no convincing answer to offer. If she were to tell Adila that something within her warned her not to yield, deterring her from buckling under, Adila would laugh at her. If she insinuated that some sort of danger threatened from the direction of Dr. Ramzi, a danger she could not pinpoint at present, Adila would think her insane.

Layla did not surrender. Dr. Ramzi went on drinking her blood, his words like a hammer in a worker’s fist, demolishing whatever resisted, day after day. His presence filled her with a fear that paralyzed her senses and yet at the same time attracted her. She could not take her eyes from him.

Layla stood up. Dr. Ramzi had asked her a question. His eyes narrowed; a smirk played on his face. Not a trace of surprise: he knew she would cave in. It was just a question of time, patience, and persistence, nothing more and nothing less. Layla spun out her response. She was alert; she attended to all that occurred around her; she was perfectly capable of perceiving what he wanted and batting his view back to him in words that almost echoed his and in a style that closely imitated his. The inexact parallel was not lost on the professor.

“Are you really convinced of what you are saying?”

Layla pressed her lips together in irritation and said nothing. A new operation was mounted. He was a sculptor plying his chisel, now delicately, now almost violently, and always with studied care. Here a light touch, here a deep furrow, here a chunk that must be dislodged entirely, and here a segment that required only refining and polishing. The lineaments of the statue emerged gradually, notch after notch, dent by dent, cut away by the artist’s will.

Layla understood nothing of this. She knew only that Dr. Ramzi had changed his manner. He had come to consider her a proponent of his school of thought, one of his followers. He had become more patient with her, more charitable of her lapses, even if he still did criticize her now and then. After all, he wanted her to learn from her errors. Layla began to chime in with Adila, defending Dr. Ramzi whenever Sanaa denounced him.

In Layla’s second year at the university Dr. Ramzi’s authority seemed to extend into areas she had considered her own personal province. One day she was turning in a paper in his office. She put it on his desk and turned to go out.

“What’s that?” he said.

Layla sensed that his gaze was fixed on her face, specifically on her lips. Gamila had invited her the evening before to an evening party and had insisted on coloring her lips. In the morning there was still a trace of it, so she had added a light layer of color. Now her face grew pink. “What’s what?”

“What’s on your lips.”

She spoke faintly as if confessing to a crime. “Lipstick.”

He concealed a smile. “I know that. But why did you put it on? You’ve never used lipstick before.”

“All the girls use it.”

“That’s descending to the gutter. Just because a wave of vulgar behavior has engulfed the city, does that mean we are all obliged to act immorally?”

His reference to immoral behavior provoked Layla. “I’m not immoral!”

He spoke coldly, apparently unmoved by her anger. “I am saying the opposite. I’m saying that you are far superior to the girls who act that way.”

“I’m not superior to anyone,” said Layla obstinately.

“You are certainly sup

erior.”

She met his gaze for the first time since entering the room. “Superior why?”

He smiled directly at her, his eyes coldly confident. “Because I believe you are.”

It did not stop at that. His eyes followed her everywhere. He would appear suddenly, as if the earth had split to let him emerge, and his eyes would rove across her before fixing intently on her, as if taking her measure, as if weighing her. There was no desire or emotion in his gaze; his calculation was slow and precise, an inspector evaluating a coin for possible forgery. Under Dr. Ramzi’s gaze Layla shivered. An obscure fear paralyzed her senses, and she always let out a sigh of relief the moment he pulled his eyes from her.

Even when he was not in sight his presence seemed to corral her. Standing with Adila and Sanaa, sharing a joke with a male classmate, she would thank God that Dr. Ramzi had not seen her. If she gave a paper in class that won another professor’s approval, she wished Dr. Ramzi could have heard her so he would have to admit her exceptional ability. Submerged in the library for hours on end, she would ask herself why he had not happened to see her devoting herself so fully to study. Why was it that he only seemed to see her when she was giggling or hanging behind to chat in a corner of the college? Why did he catch sight of her only when she was doing something she ought not to be doing? Yet occasionally she found herself able to forget his existence. That was what happened on one particular morning.

In the library’s main reading room a classmate approached Layla’s table. Would she loan him that reference book she was reading as soon as she had finished with it? As she raised her head she thought immediately of Husayn. Yes, when Husayn smiled his eyes had exactly the same look: the boldness, the fierce hardness seemed to melt, and his eyes became as soft and dream-filled as these big, black ones she saw before her now. Smiling, she promised her classmate the book. He pulled out the chair next to her and sat down. He admired the way she spoke in class, he said, and he liked what she had to say. He wrote poetry, and he would be very pleased if she would agree to read some of his poems. He began to chat about the future, the poetry he hoped to compose, his ideas about poetic innovation, and how he could steer clear of the chasm that now existed in Arabic poetry between form and content . . . .

Layla sat back, at ease, listening to him; lowering her eyelids, she tilted her head to one side, a diminutive smile on her lips. She could so easily imagine that it was Husayn she heard. When he talked of the future, Husayn’s voice rang out richly, too, a dreamy timbre creeping into it. Husayn’s words pulsed like this, with a life of their own, an energy his listeners could not help taking in, their thoughts inevitably soaring with his as that voice bore them upward.

“Have you seen this book?” The voice was icy, sharp; a book appeared from nowhere, shoved across the table toward the two of them. Layla’s eyes flew open; Dr. Ramzi faced her. Her classmate jumped to his feet but she could not. In fact, she could not even see; she was dizzy, as if she were falling from a great height. Her classmate leafed through the book; could he borrow it? he asked Dr. Ramzi. No, said their professor; he had put a copy in the library but it was not yet catalogued. He would not loan this one; it was his own personal copy. “And I like my books to be very clean. I do not appreciate having anyone touch them. When that happens to a book I can no longer read it; I cannot feel that it is truly mine.” As he spoke, Dr. Ramzi fixed Layla with his gaze. But if his words were to carry more than one meaning, Layla was not in any condition to perceive it. Fear numbed her, as if she had been caught red-handed in a capital offense.

Dr. Ramzi tried to get her to meet his eyes. “Miss, have you seen this book?” But Layla did not raise her eyes. She put out trembling hands and slowly drew the book to where she sat, and tried to focus her eyes on its cover. Dr. Ramzi turned to the bookshelves lining the nearby wall. Her classmate excused himself and left the reading room.

She longed to leave, too. But she could not; she must wait until Dr. Ramzi retrieved his book. He stood at the shelves for what seemed a long time; ponderously, he went to the librarian’s desk. Layla could almost feel his slow, heavy steps crushing her nerves; he was drawing out his conversation with the librarian to lengthen her torment, she was certain. He returned and saw at once that she had not touched the book.

“You did not open the book? And why not? Are you that embarrassed?” This time Layla did pick up his double meaning. Her face reddened.

Dr. Ramzi’s treatment of Layla underwent another perceptible change. Encountering her in the corridor, he would turn his eyes unhurriedly away, no longer confronting her with that calculating gaze, as if he had discovered that the coin was forged after all and did not even deserve to be assessed. In class, he turned on her; his tone was markedly harsher, as several of Layla’s classmates, female and male, commented.

“What is that man’s problem?” Sanaa asked. “Can’t he leave off?”

“I can’t stand any more,” said Layla. “Enough abuse! And anyway, I’d really like to know what it is he wants from me?”

Adila stopped in her tracks. Her voice hinted that the thought that had just come into her head was nothing short of brilliant. “Mightn’t he be in love with you, Layla?”

“Get out of here. Have you lost your mind?”

Sanaa laughed. “What kind of lousy love is that? That’s hate, not love.”

But the idea had captivated Adila. She was ready with one of her poses. “Why not? Did not the famous philosopher Schopenhauer say that love, deep down, is really hatred? And hatred, in its depths—is it not love?”

Layla and Sanaa burst out laughing. Choking back her tears, Sanaa said, “Right—just like when you open a barrel from one end and it’s honey. Then you open it from the other end and you’ve got tar.”

“That’s enough clowning around,” exclaimed Layla. “Come on, let’s find a place to sit. We’ve got to think of some way out of this.” The friends headed for their preferred spot on the grass behind the library. Adila, her face serious now, turned to Sanaa. “But I really don’t think I’m crazy. Can you tell me why that man chases her everywhere? And why he is so fond of upsetting her?”

“Do tell, madam cleric.”

Adila tried to hold back her triumphant smile. “I swear, he’s in love with her.” She turned to Layla, her eyes gleaming. “He ought to be! If he marries you, Layla, now that would be some marriage!”

Sanaa’s response was a theatrical flourish. “God preserve us!” Adila tilted her head quizzically and addressed Sanaa again, enthusiastically, as if Dr. Ramzi had indeed proposed to Layla. “So? What’s wrong with it? Is he so bad? Fantastic professor, good looks, has a car, people know who he is, he gets respect. A groom any girl in the college would hope for.”

“You’re awful,” said Layla. “Now come on, girls, be serious. What are we doing? Stay on the subject. I have to find some way of handling this.”

“It’s simple,” said Sanaa seriously. “There’s only one solution.”

Layla looked at her curiously.

“Marry him.”

Layla burst out laughing. Adila seemed less pleased. “What’s your problem? Why are you in such a tizzy? Now, this match isn’t—” Layla interrupted her, tears of laughter still pouring from her eyes. “Adila, stop it! What on earth brought the subject of marriage and all that nonsense into this? How ridiculous can we get?”

But Adila was entirely elsewhere. Her notion had graduated to firm belief, and she began defending it as established fact.

“Fine, tell the truth, ya sitti—now wouldn’t you want to marry him?”

“Perish the thought.”

“Are you going to find anyone better than him to marry?”

“Of course.”

Mahmud’s image shot into Layla’s head. Next to Dr. Ramzi he seemed a midget next to a giant. She was not at all happy about this unbidden comparison.

Sanaa leaned over toward Adila and said quietly, “You know something, Adila? Whoever marries Dr. Ramzi—now what kind

of life do you think she will have?”

A look of interest came into Layla’s eyes as she listened to Sanaa.

“Whoever marries him will be put in the deep freeze and locked up. Jammed in a tin of sardines and sealed.” Layla shivered. But Adila slapped her own cheek melodramatically. “Horrors . . . .”

Sanaa went on. “And personally, I have no desire to live in a deep freeze. I want to sail . . . .”

“Sail? Through the air? Like this?” Adila spread out her arms and flapped them up and down. Sanaa tried not to smile. “Yes.”

“Okay, girl. So he might make you soar. What’s the flaw in him?”

Sanaa’s voice was flat. “Make me soar—he would smother any woman to death.”

“Oh stop being ridiculous. By God, tomorrow the whole college is going to envy Layla.”

Layla laughed. “Adila, you’re the one who should stop being ridiculous. So we can find a solution to this.”

“I have a suggestion,” said Sanaa. “Adila can talk to him when she goes in to deliver her paper.”

“What is she going to say to him?”

“She can say, ‘Why the mistreatment, apple of my eye? Release her, I beg of you for God’s sake, and for the sake of love.’”

Now it was Adila who burst out laughing as she tried to imagine herself standing before Dr. Ramzi’s solemn face and saying these words.

“I’m leaving,” said Layla in irritation as she got up. Sanaa pulled her by the arm. “That’s all, now I’ll be serious. Adila can say to him, ‘Layla apologizes if she did anything wrong, and she begs you to forgive her.’”

“That’s more reasonable,” said Layla. “But forget about the ‘forgive her’ part.”

“And who said I’m going to talk to him about this anyway?” said Adila, cutting Layla off. Layla’s face fell.

“Don’t get upset,” said Sanaa. “I have another suggestion.”

“What?”

“Adila can marry him.”

The Open Door

The Open Door