- Home

- Latifa al-Zayyat

The Open Door Page 16

The Open Door Read online

Page 16

“Come on, let’s go—right now.” She plodded to the door, brushing right by Gamila, who stood motionless as a statue in her white dress, her back to the sky, a portrait framed in the ropy, ugly masses of smoke.

*

That evening, Mahmud went to jail. With many other irregulars, he would stay in detention for six months. As the sentence wore on, Layla’s father intoned an unchanging refrain. “I knew it. I knew this would be the end of it all.”

And as the sentence wore on, Layla’s entire existence was concentrated in her effort to conceal her turmoil from all of them. She went on as usual: talking, laughing, behaving as she normally did. At the end of each day she would return to her room in utter exhaustion, an actress whose spell onstage had gone on far too long. Stretched full-length on her bed, she ached through every part of her body. It was a pain whose source she could not exactly pinpoint. Her mother always referred to this sort of fatiguing ache—whose exact location you could never really figure out—with the same phrase: “My body is defeated.” Yes, that’s what it was; her body was defeated. And not just her body: everything. Everything inside of her was defeated, as if she had hefted a load that was really far too heavy for her capacity, and it had fractured her spine.

Wasn’t that what she had done, in fact? For she had challenged her father and posed a threat to her mother. She had flown in the face of their accustomed practices, had rejected their most fundamental beliefs. She had fallen in love. And then, she had been so determined to abandon their narrow world for a world that was alive, a world vast and wide and full! She had wanted—had willed—that she and Isam would build a world of light. In their world all would be beautifully transparent, authentic and basic, so unlike the world she knew. Theirs would be a world of love; it would be the beautiful world of truth. And then what had been the result of it all? Coffee spilt on the carpet; a darkened kitchen; a defeated body; earth, mud—nothing but the soiled surface of that world she had tried to flee.

And Mahmud? Mahmud had challenged and threatened them, too. He had gone, he had left, he had broken defiantly out of their world to sail, laughing and sparkling, into a world of . . . of love, that world of love, truth, and beauty. And he had returned crushed, cowering, withdrawn, his wings more than clipped. Filth had filled his eyes, filth and mud; the mud from which he had fled. And a fire encircled the city, the country—black, acrid smoke, and a darkened prison, and a world narrower than the one he had burst from so determinedly to sail beyond, laughing and sparkling. No. To sparkle was not the lot of her brother, nor was it her lot. To sparkle was the province of Gamila alone.

With radiant triumph Gamila’s eyes made a slow, careful circuit. “Really, Layla? Does the dining room set really please you?” She did not bother to wait for an answer; Layla, she knew well, had never in her life seen the like of this. Her aunt, she was well aware, was staring round in stunned delight—like a woman just come in from the village, thought Gamila with a flash in her eyes, visiting Cairo for the very first time. Her aunt’s husband was silent; this was the only way, she was certain, that he could hide the embarrassment and agitation he must be feeling.

From the huge window, the sun’s rays cascaded in, setting the redness of the carpet on fire, and glinting against the marquetry work of the mahogany buffet. An almost painfully intense greenness pulsed upon them from the garden beyond the window, breaking the carpet’s ardent red. Sitting at the head of the table, Gamila beckoned the sufragi lightly, naturally, as if she had been doing so her entire life. The man walked all the way around the table to her side. Gamila spoke to him in an undertone, relaxed, smiling, animated, her hand toying with a diamond collar that circled her neck. At Layla’s arm, the sufragi bowed slightly as he offered her the plate—a pyramid of cassata sheathed in preserved fruit. Isam’s eyes flashed as he looked at her with a smile. “Take another chunk, Layla,” he said. “You’ve always loved ice cream.”

He sat down to eat his own cassata with relish, at ease in his chair. He no longer felt any discomfort in her presence. At first, when she had ended their relationship—and before he’d understood why—he had felt vexed indeed. When he realized that she knew, his chagrin vanished, though, for why should he feel at all embarrassed now? His conscience was clear and clean, his thoughts as transparent as the crystal goblets gleaming on Gamila’s table. He had done what he truly believed expressed his obligation to her; after all, he had saved her from something that made death look positively bearable. Anyway, there had been no other solution; and if he had acted any differently, then inevitably he would have harmed her. And he would find it infinitely easier to die than to harm her, when he loved her so, and always would.

But what Layla found so painful was Isam’s behavior. Why, he acted still as if he sincerely loved her! It bewildered her. How could he possibly love one woman with his soul and another with his body? And anyway, what about that other woman? Had it never occurred to him that she was a human being, too? That he had harmed her bodily and emotionally, that he had threatened her humanity? No, clearly it had not occurred to Isam, not at all. He seemed completely confident and at peace with himself. His face bore a new expression—the grieved look of the martyr to duty.

Yes, indeed, Isam was confident and at peace. And Gamila—well, she went far beyond confident! Gamila was proud; she was splendid; she was smugly victorious. She had accepted life as it was, and simply, without creating any complications. Gamila had not stopped to philosophize. She had listened to her mother and she had followed sanctioned practice. She had followed those fundamentals. And therefore life had been good to her. Life had offered its bounty, its contentment, its security.

There had been a time when she had regarded Gamila with a touch of disdain. She had considered herself stronger than Gamila, than her aunt, than her father—and stronger than their beliefs, their rules, their traditions. She had laughed with a certain superiority when her mother had said, “The one who knows the fundamentals does not suffer.”

Yes. She had existed for a time in the shadow of this silly illusion. But in truth it was she who was silly, trivial, conceited, and despicable. She was the doormat beneath people’s soles.

Chapter Ten

JULY 23, 1952. MORNING. THE army had shaken Egypt to the core. Awe, disbelief, a belligerent joy and pride; as news of the revolution spread, new sentiments trembled on millions of lips and shone through the tears in people’s eyes. New words sobbed from throats choked with emotion. Egyptians poured from their homes to fervently clasp the hands of the soldiers, hearts sheltered in their cupped and shaking palms.

Muhammad Effendi Sulayman sat at home, riveted to the radio, listening again and again to the declaration of the Revolutionary Leadership. He was petrified by the conviction that something would intervene to thwart the revolution and postpone Mahmud’s release. At first he had not believed his ears. He simply could not accept that men like him—Egyptians just like him—had successfully challenged the authorities—all of them!—and had overturned the government. When it finally dawned on him that the thing had really happened, a wave of pride in himself, in having been born an Egyptian, engulfed him.

But a different reaction followed all too soon. An agonizing fear throbbed through his body as he heard that the revolution had moved into a new stage, and it mounted as he heard that they were talking about dethroning the king. Wasn’t the earth still turning? he asked himself. Well, then, mustn’t the king still be on his throne, the Egyptian people bowing as always to his sovereignty? How could those revolutionaries change the course of destiny? Glued to the radio, Muhammad Effendi Sulayman listened to the news of the king’s expulsion from Egypt. Tears collected in his eyes, reflecting the blend of alarm and pride he felt as the paramount icon of the old Egypt was demolished before his eyes.

As Muhammad Effendi Sulayman heard the momentous news, Layla was walking along Qasr al-Aini Street. She noticed a blue-overalled worker on a bicycle coming in her direction; still at a distance, he was waving his

hands wildly, turning first to one side and then the other, flinging out words that Layla could not make out. She could see, though, that people were coming together, forming little groups and chattering. A few meters from Layla the bicycle rider stopped, his swarthy face wreathed in smiles as he looked at her. Gesturing wildly, he yelled, “The king has left the country!” and then turned away immediately to offer the same news to a barefoot boy who was dashing toward him. Layla felt a quaking in her body and took off at a run after the worker. People darted from their shops to crowd around him, asking for more details. “The king has left the country!” The worker’s ecstasy encompassed his whole face. Layla’s hand shot out and he shook it vigorously with a simple “Congratulations!”

“Congratulations!” The word resounded as if people were incapable of finding any other. Spaces between bodies vanished as one person clapped the next on the shoulder, as people chuckled and whooped and told jokes. Layla could not move; she stood among them, enjoying her sense of oneness with the crowd, the companionable sensation that they had all contributed in one way or another to expelling the king. A mood of sympathy, of ease and belonging, swept over her, a sense of confidence in herself and others; how she wished she could stay among them, stay on and on! But the moment passed; the bicyclist straightened on his seat, warning people that he was about to move on; folks tried to detain him but he would not stay. He moved forward, waving his hands, laughing, to go on to others, to tell more and more people that the king had been thrown out. Forward he went, from one group to another, as if propelled by a crying need inside of him to connect with the greatest number of people possible at this precise moment in time.

It was a pounding forceful enough to shake even the massive doors to the Aganib Prison, where many of the guerillas were imprisoned. It was like the blow of a single man, in unison like the shouts with which it mingled: “Long live Egypt! Long live the Revolution! Down with Imperialism!” It was a moment when those young people surely could have broken down those doors, but there was no reason to do so. They understood that the prison doors were as good as open; they knew they were all but free. It was just a matter of days. Yet those young souls could not bear it! At such a moment, were those doors to keep them apart? At this moment, for which they had waited all their lives, indeed for which they had lived? They were determined to be together, united, and the prison shook with their blows and cries. It was not the usual time to organize themselves into rows for the officers; but the prison superintendent issued his order to open the huge doors. Prisoners and jailers—they hugged each other, laughter and tears mingling. A prisoner twisted a jailer’s belt around his middle and began to dance. A crowd gathered round him, clapping in time, while other prisoners split into groups, talking and laughing. A voice rose in song.

My country, my country

My blood I’ve offered you

I’ll sacrifice my life

For the peace that is your due.

Silence—and then other voices rose, and still others joined those, as their youthful owners stood tall and the circle widened to embrace them all. The voices combined to become one voice—a single, strong voice of celebration that arched across the land of Egypt to embrace every one of its folk.

*

Mahmud and Husayn strolled through the yard that lay behind the Aganib Prison. “Didn’t I tell you?” exclaimed Husayn. “Now maybe you’ll start believing what I say!”

Mahmud smiled, shaking his head in wonder. “But who could have imagined it? Who could have foreseen that things would develop like this? And so fast?” As the friends approached a wooden bench, Mahmud dropped onto it and stretched. He felt deeply refreshed, as if an enormous responsibility had suddenly been lifted from his shoulders; as if he had delivered that burden to another and dusted his hands of it; and now it was his turn to rest.

“What’s on your mind right now, Mahmud?”

Mahmud’s hand, no longer tense, stroked his growing beard. “A good shave, a warm bath, and a clean mattress.”

Husayn snorted. “What a lucky guy you are! You’re going back to an orderly household, all waiting for you—to your mother and sister. Speaking of your sister—she’s awfully nice.”

Mahmud looked at him. “Why don’t you get married, Husayn? Instead of living by yourself like this.”

Husayn started laughing. Then he raised his head. “I’m broke, ustaz.”

“Two years an engineer in a good, solid company, and you’re broke! You’ve got to be kidding me. How much were you getting?”

“Thirty-five pounds.”

“You didn’t save any of it?”

“I saved.”

“So?—”

Husayn smiled and shrugged. “I married off my sister—got her off my back.”

Mahmud leaned over and clapped a hand on Husayn’s thigh. “But you’re no ordinary guy. And can’t you take up the scholarship your sister did the paperwork for?”

“I don’t want to leave the country right now.”

Mahmud pulled himself upright. “Oh come on, Husayn, what’s the matter with you? Sure, the first time around you pulled out of the scholarship, and your excuse was perfectly reasonable and acceptable, and they knew that. There were circumstances, and a guy couldn’t leave the country at such a time. But now—it couldn’t be a better time. So—?”

“A month or two, that’s all, until things settle down. Mightn’t they need us?”

“They? Whom do you mean?”

“The revolution.”

“Why?” Mahmud’s voice was sarcastic. “Are they going to appoint you as a Minister of Public Works, or what?”

Husayn began to laugh but stopped short as he leaned toward Mahmud. His voice was serious. “Mahmud, we’ve got to be alert. The English aren’t going to take this lying down. They aren’t going to watch the country slip from between their fingers like this without putting up a very big fuss.”

Mahmud did not seem bothered. “In any case, our responsibility stops here. Now it’s up to the army.”

Husayn was silent for a moment, gazing toward the horizon. He spoke quietly, as if thinking out loud. “We’re all responsible. As long as one’s alive, his responsibility toward his country never comes to an end.”

Mahmud got to his feet. “Fine, then, just stay here and languish, lazybones,” he said, irritated. “Anyone with your attitude doesn’t deserve to travel, anyway.”

Husayn’s face reddened at the sudden, unexpected insult. He bit back the sharp words on his tongue. He truly loved Mahmud, and he knew how intense had been Mahmud’s transformation while in detention. His friend had sketched such a rosy picture of life in his head that confronting its rawness shocked him. Death he could face with courage, but he had not been able to face treachery so peaceably. He had witnessed betrayal at the Canal, and in the burning of Cairo, and in the wave of arrests and detentions. The world had frightened him and he would never quite recover. Now, he turned to his friend.

“I’m sorry, Husayn.”

Husayn gazed into his companion’s gaunt face, aged by deprivation, the eyes permanently bewildered, the look of a child unthinkably deceived. He smiled, stood up, and put his arm around Mahmud as they headed toward the prison’s reception area, trying all the while to think of something to say that would dispel Mahmud’s worries. Husayn knew he had clubbed his friend in a sensitive spot at the worst possible moment. He had reminded Mahmud of responsibility at a time when his friend believed he had finally rid himself once and for all of that burden. The revolution had come as a salvation from on high for Mahmud, a rescue that lifted from his weary back the necessity of facing life in its merciless realities; a salvation that gave him to believe that he could finally stand on shore, a mere observer, without the slightest feeling of guilt. Husayn smiled and leaned toward Mahmud.

“I’m bad news, aren’t I?”

Mahmud broke out laughing and disentangled himself from Husayn’s grip. But Husayn grabbed his arm again and quickly went on. “Mahmud,

there’s something I want to talk to you about, something personal.”

Mahmud stopped laughing and looked straight at Husayn, his eyes showing interest. “What’s going on, Husayn?”

Husayn hesitated a moment. The smile disappeared from his face, his hand dropped from Mahmud’s arm, and he took a rapid step forward.

“Husayn, what is it? Come on, say something, brother.”

Husayn would not meet his eyes. “Later, Mahmud. Later on.” His voice dwindled. “It’s my problem, and I’m the one who has to solve it.”

Husayn tossed and turned on his straw pallet, settled on his back and lay still, thinking. Why had he used the word “problem”? Why not, for example, “subject,” or “issue,” rather than “problem”? But wasn’t one-sided love a problem indeed? Especially when you didn’t even know if the girl you loved was attached to someone else or not. No—she isn’t attached; she was, she really was, but everything ended. That was clear, very clear from the way she had pushed Isam’s hands away from her body, as if they held some filth that she absolutely could not bear to have within reach. No—this was no ordinary quarrel! It could not have been. It was the end of their relationship, an end that bastard deserved.

Husayn smiled lightly in the darkness. What right did he have to cast names at a person he knew only by sight? Someone of whom he knew so little? Wasn’t this madness? But wasn’t the whole story madness and more madness? What did he know of the girl who had occupied every moment of his life in this prison? A girl to whose image he fell asleep and wakened? Who filled his heart with her radiance and an enthusiasm for life? Nothing—he knew nothing at all. Yet the sensation persisted that he had known her all his life—and would never know her any better than he already did today, because it would be impossible to know her any better. He was sure that he could finish whatever sentence she started, could turn automatically in the direction she wanted to go even before she could do so. And he had known this after spending no more than half an hour with her! Well, perhaps it was the prison. It was this solitude, this loneliness, that had constructed from one fleeting meeting a whole legend to consume him, a fairy tale that started to fade whenever the light of day brushed over it. If he were to leave prison, perhaps his feelings would change? No, never—that would never happen. He had sensed the extent of his attachment to her even before prison; in fact, he had known it the moment he saw her. What had happened was beyond anyone’s understanding. You couldn’t explain it to anyone; it could not be subjected to any logic or rational explanation. But it had happened, and it had happened to him—to someone who was never convinced by anything that wasn’t completely logical or rational or scientific. When she had rushed toward him in the elevator he had barely been able to keep back a shout. She had stopped and apologized, and into his mind had sprung a wholly-formed question: “Where have you been all this time? I’ve been waiting for you all my life!” Meanwhile, his tongue had formed meaningless utterances that had absolutely nothing to do with the thoughts coursing through him. And then he had left her, he had come out of the elevator. But when she had shut the iron grille between them he realized that he could not just leave her and go away. She was his fate and he could not let go of that. Then, when he discovered that she was Mahmud’s sister, he realized that he would see more of her. Still, as the elevator ascended he had felt that a part of him was going with it. When his eyes had met hers and they had laughed together he imagined that perhaps she, too, had understood that he was her fate, but he’d been wrong. The two of them were worlds apart.

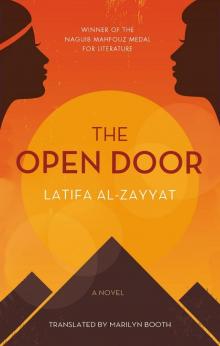

The Open Door

The Open Door