- Home

- Latifa al-Zayyat

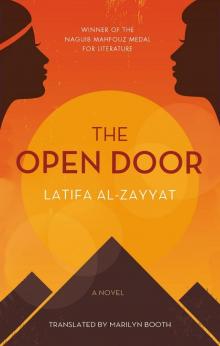

The Open Door Page 12

The Open Door Read online

Page 12

Still sniffling, Gamila said, “simone.”

“And the shoes?”

Gamila wiped away the tears with the back of her hand. “Satin, same color as the dress.”

“So that’s it. Tomorrow morning I’ll go out and get the lace and order the shoes. But come tell me what you think about this now so we can finish up. Time is going fast and we only have a week until the engagement.” Samira Hanim dragged Gamila by the hand, her gaze distant as if dreaming as she spoke. “Anyway, after the engagement you’ll really need all of these dresses. One day at the Auberge, one day at the Mena House, and then the Hilmiya Palace . . . .”

Gamila giggled. “Mama, that’s enough. But I just don’t want that gray. It’s a dead bore.”

Dropping into the armchair, her eyes steadily on the door, Layla spoke. “No, Gamila, it’s just the opposite. It’s a restful color, and very attractive.”

Her aunt perched on the edge of the bed. “Not only restful, Gamila, that gray shows off a woman’s shape really well. It’s not the color the man’ll look at—he won’t even notice that. What he will notice is the body—your figure.”

Layla tried to keep from smiling, while Gamila laughed. “Mama, you see everything, don’t you? You are so au courant!”

Samira Hanim chuckled and gave her daughter, sitting across from her, a little slap on the thigh. “So where is Isam?” she exclaimed. “He has very good taste in dresses. Go call him, Gamila. No, wait, help me roll up the cloth so it won’t wrinkle, and Layla can call him.”

Layla stood up.

“You’ll find him in his study, Layla,” said her aunt.

As she closed the study door behind her she felt a swell of aching affection surge over her. Isam was at his desk, head buried in his hands. Layla paused, observing him, then tiptoed closer. She patted his shoulder gently but, as if he were submerged in a deep sleep, he did not react. She bent over him and whispered. “Isam.”

The voice startled him; he twitched and raised his head. Layla shot up, alarmed, but he seized her arms with both fists before she could step back. His face seemed different, as if its outlines had partly dissolved: the nose seemed broader and flatter, the cheeks sagged. His chin was slack, his mouth loose; his eyes were vacant, as if he were not wholly conscious. He seemed to lift his body ponderously; his tight grasp fixed her to the floor. Now his features began to sharpen, to gain both strength and harshness, while his blank gaze settled and gradually took focus, but with an expression of threat and determination; she wondered if he was going to slap her. His hands were tight on her upper arms, his body towering over her, his clouded face touching her face, his lips falling heavily on to hers. Layla threw her head back and let out a choked scream. “Isam—”

He gave no indication of having heard her. His face did not relax; his eyes remained hard. Layla backed away—one step, another—but Isam followed her step for step. She glanced over her shoulder and tried to alter the direction she was moving, but Isam held her arms more tightly and directed her toward the empty space between the chair and the wall, forcing her against the wall.

“Let go, Isam. Let go!”

He still seemed not to hear anything. He lowered his hands slowly, still on her arms, and seized her hands. He brought his body close to hers. Layla jerked her head as far back as she could, to the wall. A cold shiver ran through her limbs and her lips trembled. “Isam, I’m going to scream. I’ll scream, I will, Isam.”

Isam crushed her body with his and brought his parted lips down over her eyes. He stroked her cheek slowly, then suddenly moved his lips to her mouth. Her lips froze; Isam’s tears wetted her cheeks. He fell into the chair, jammed his elbows onto his thighs, supported his face in his hands, and broke into sobs. His sobbing rose gradually as Layla stood rooted to the spot, her body and mind vacant, desolate, as if she had just awakened from a dream, her mind blank. Isam’s crying, loud in her ears, reverberated with the terror and embarrassment that overwhelmed her. Had she committed some awful deed, entered a sacred place where she had no right to be, seen something inviolable that she had no right to see? She longed to be away from this place; she yearned to escape. Isam’s wailing filled her ears. She reached out a shaking hand that stopped, hesitant, in midair and then came down gently on Isam’s shoulder. He spoke, his voice interrupted by sobs.

“You despise me, don’t you?”

“Shh, Isam,” Layla whispered. “Shh, quiet down. Please. That’s enough.”

Isam pushed her hand from his shoulder and looked at her in loathing. When he spoke his voice had grown steady. “Go away. Leave me alone. I don’t want to see you. I don’t want to see you at all.”

Layla pressed her lips together and ran out of the room.

She sat in her bedroom, busy with a jacket she was knitting. Her father was out; her mother was upstairs, visiting her sister. The maid came in. “Mr. Isam is outside, ya sitti.”

Layla’s face grew hard. She dropped her knitting, walking toward the window, her back to the maid as she spoke. “Tell Isam that Mama is not at home.”

“I told him that, madame; he said he wants to see you.”

“Tell him I’m asleep, Fatima.”

“Careful, Fatima,” said Isam, pushing the young girl gently away from the doorway as he entered. Layla did not move. She held her head straight and absolutely still, her back to Isam. After a moment’s silence, she spoke coldly. “What do you want, Isam?”

“I—” She could hear him come nearer. “I’m sorry, Layla, about everything that happened.”

Layla turned around slowly. Isam’s pale skin was blotchy and sallow, and deep black circles shadowed his eyes as if he were recovering from a long illness.

“Okay, Isam. Consider the subject closed.” Her voice was flat.

Isam’s nostrils trembled. “What subject?”

She did not answer. She sat down on the edge of the bed and put out one trembling hand to her knitting. She slipped the needle into the stitch, brought the yarn round it and pulled the new stitch over the old. She slipped the old stitch from the needle and began again. Isam came nearer.

“What do you mean, Layla?” His voice was gentler now. Layla pulled the yarn so hard that it broke. She threw the knitting down on the bed, irritated.

“The relationship between us. Consider it ended.”

Isam narrowed his eyes on the knitting. He leaned down and started to pick it up with both hands, but his grip loosened and he let it fall back onto the bed. He turned and shuffled, his shoulders slumped, to a small table. He leaned his palms heavily on it and spoke faintly, as if talking to himself. “I knew you wouldn’t forgive me if I didn’t go with Mahmud.”

Layla yanked the piece of knitting back onto her lap and nervously slipped it off the needle. To reattach the broken yarn she began to undo part of what she had knitted, her right hand jerking from left to right repeatedly. Then she discovered that she had unraveled more than she had intended and she dropped her hands into her lap, folded motionless over the piece of knitting.

“Isn’t that what you wanted?” Her voice was bitter.

Isam was silent, motionless, his back still to her.

“So, you have nothing to say?”

Isam turned to face her; his skin seemed even paler. “If you could only imagine.” His voice got fainter until it was barely audible. “If you could only imagine how much I love you.” Tears glistened in Layla’s eyes. She averted her gaze and tried to speak, her voice choked. “You don’t love me. If you loved me you wouldn’t have done what you did upstairs.” Layla got up, the knitting falling from her lap to the floor. She faced Isam.

“Why?” Her voice was sharp, threatening. “Why did you do that?”

“Because I love you.”

Layla’s laugh came out more like a moan. She walked to the window and pressed her forehead against the pane until it hurt. “Do you know, Isam, what I was feeling, the whole time? I felt like you wanted to hit me.” She turned to him but stayed close to the window.

“No, Isam, that isn’t love. Call it anything you want, but not love.”

Isam sat down on the armchair across from her bed. “You’re still too young to understand anything.”

“I’m not too young,” said Layla, stalking toward him. “And I do understand. Everything. And I still say it isn’t love.”

Isam raised his head. “What do you understand?” His voice was quiet and bitter. “That love is this thing you read about in novels? That I can’t sleep, can’t study, can’t live? D’you understand the agony I feel when you’re next to me and I can’t even look at you, can’t touch you?” Again his voice grew fainter and fainter, and he bent over, his eyes on the floor. “And when I’m away from you, I tell myself, Layla was with me but I didn’t see her, not enough, and then I feel like I’m going mad, I feel like someone shut up in his cell. So then I come back, and what happened before happens again.” He raised his watery eyes. “You know, Layla, what it’s like? Like you’re in the desert, digging just so you can find a single drop of water, and you go on digging, and then you say, now, now I’m there. No—just a bit more, and I’ll be there. Next time. And the further down you get, the more imprisoned you become in the hole you have dug, and you never do get there. And the water never appears. It just never does.” Isam struck the chair with his fist. He jumped up to face Layla, still speaking, his voice full of anger and sarcasm. “Can you possibly understand those feelings?”

Layla fixed her eyes on the floor. She caught sight of the knitting, fallen there. She went over, bent slowly and picked it up, straightened slowly, and put it on the bed.

“Isam,” she said calmly. “You did kiss me one time before, didn’t you? Can you tell me why I wasn’t afraid that day?”

“Because that day you loved me. Today, you don’t.”

Layla made a gesture of disavowal. “Nonsense. My feelings about you haven’t changed. Do you want to know why I wasn’t afraid that day, Isam?”

Isam compressed his lips and sat down again. Layla was pacing the room.

“That day there was something. Something in your hands, in your face and eyes and movements. Something that made whatever you did okay—and not just okay. Okay and very nice.” She stopped right in front of Isam. “That day, there was love. But today—today you were looking at me as if I was your enemy, as if you wanted to win some victory over me. Why? Why, Isam?”

Isam covered his face in his hands and did not respond.

“Why did you treat me like that?” Layla asked, her voice unsteady.

Isam got up and walked toward the window. Her outcry seemed to exhaust Layla, and she collapsed onto the edge of the bed, repeating in a faint voice, “Why? Why?”

Isam turned and walked over to her. He leaned over and rubbed her shoulder gently and whispered. “I’m afraid, Layla. Afraid. Since the day Mahmud left, I’ve been afraid. From the moment you closed the door in my face, afraid, afraid you’d slip away, afraid I’d lose you. That fear has been driving me insane. It puts me in a state where I have no control over my actions.”

Layla averted her face again but he went on doggedly. “You can be sure that if I’d been in my right mind I never would have gotten that near to you. You can’t imagine how hurt I am by what happened.” He paused. “Maybe if you knew that from the day we began to love each other, my conscience has been tormenting me, and all the time I feel like I’m doing something wrong, that I’m betraying a trust people have put in me—maybe if you realize that, you can imagine how awful I feel now.”

Things began to fall into place. Isam’s behavior had so bewildered her at the time, but now she realized why his face would go red whenever her father came into the room where they were, or Mahmud, or her mother. He considered her their property, and so he felt embarrassed, ashamed, as if he were wronging them by loving her. The feelings that had filled her with pride and happy expectation and a new desire for life—with a belief in herself—filled him with a sense of guilt. Her face darkened. “If you feel like you are wrong because you didn’t go to the Canal, then why don’t you go now, Isam?”

Her question startled him. He quickly raised his hand from her shoulder and straightened up, his demeanor angry. “I’m not wrong. You know perfectly well the circumstances that prevented me from going.”

Layla cut him off coldly. “Mahmud had circumstances, too, yet he went.”

“So that’s what you’ve been wanting to say to me all along, isn’t it?”

“Me?—” Isam interrupted her. “Tell me. Talk. Say that you have stopped loving me because I’m not a hero like your brother.”

“I didn’t say anything stupid like that.”

But Isam was now so angry that he could hear only his own voice. “Who do you think you are, to be able to insult me like that? Who do you think you are, to despise me like this? I’m not your slave and I’m not your brother, either. I’m free, do you understand? If it was because I love you—because I did love you, then consider the subject closed. Totally closed.” Isam stood up, trying to regain his breath. “I’m sick of this. I want to love a regular girl, who thinks like girls think, and feels like they do. I’m sick of you, and of your philosophizing, and your moods.”

Layla bent over and hid her face between her hands. “Fine, Isam. It is all over. You can go now.”

“Of course I’m going. What do you think? That I can’t live without you?”

Layla pulled her hands from her face and stood up, her color gone. “Go.”

Isam looked at her, hesitated a moment, then went out and slammed the door behind him.

Her face set, Layla sat down again on the edge of the bed and pulled her knitting over. She tried to jab the needle into the undone stitches but her hand was shaking so hard that they kept slipping out. Stubbornly, she tried again, defiantly, as if her whole self was concentrated in this single attempt.

The door opened. Isam stood in the doorway rubbing his chin for a moment before he spoke in a faint voice. “There’s just one thing I want to know, and I think it is my right to know. It is my right to know exactly where I stand at the moment.”

Layla didn’t answer; her eyes remained fixed on the piece of knitting, her hands busy trying to put the stitches back on the needle, as if she had not even heard him. Isam stepped inside the room.

“There is one question I want you to answer. And if the answer is no, I promise you you’ll never see my face ever again.”

Still, Layla said nothing. Isam walked forward until he was directly facing her.

“Layla, do you love me or not?” He seemed to choke on the words, and turned his face away. Layla pressed her lips together and tears blurred her vision. She set the knitting down on her lap. Isam bent over her and put a hand on her shoulder.

“I’m sorry Layla. I’m sorry about everything. I really can’t do without you. I can’t live without you. Please, please reassure me.”

Layla closed her eyes and the tears spilled out.

“Just one word, Layla, I don’t want any more than that. Did your feelings about me change because I didn’t go?”

Lips pressed even harder together, eyes still closed, Layla shook her head hard.

“It’s just like it was before? Just like before, Layla?” Isam’s voice shook.

Layla nodded, without saying a word. Isam’s face cleared and he bent over until his face was close to hers. “Just as much? As much as I love you, darling?”

Layla smiled and opened her eyes. Isam looked at her for a moment, tenderness shining in his eyes, and then he brushed her hair with his lips.

Chapter Eight

FOR THE NEXT FIFTEEN DAYS Layla felt as though she was trying to live at the vortex of a whirlwind, or as if she could not emerge from an intensely disturbing dream. But everything that conspired to keep her in this state of extreme nervous tension ended. All of it—thank God.

For the whole period leading up to Gamila’s engagement party, Isam acted like a madman, and Layla felt nothing but fear and terror toward him. On t

he eve of the party his insanity reached new heights; and then he stayed away from her for five entire days.

At first she truly thought she could be understanding. He seemed so afraid of losing her, and whenever she gave him a simple reassurance of her love, his fear would vanish. So she tried to reassure him at every opportunity. But she soon realized that her words were no use. He would sit like a statue, only his eyes harboring determination and threat; she feared constantly that he was about to hit her. Her mother noticed his odd behavior, and her aunt began to perceive something as well. Gamila, too; but he didn’t sense any of that. It was as if he were completely unconscious of the world around him. The bizarre expression never left his eyes. In those moments when they were alone together, he would act like a man going under, exclaiming in despair, “We must find a solution.”

Then he thought he had found the solution, and at once he appeared more self-possessed. He suggested that they get married immediately. He said he had been thinking about it for a long time and had figured out that it was indeed possible. He could take on some extra work on the side, in addition to his studies; and the added income, on top of his present stipend, would be enough. From the practical point of view nothing would change, really. All that would happen would be that she would move in. The apartment was big enough for all of them, especially since Gamila would be getting married and moving to her husband’s home. It was all very natural, simple, and reasonable.

Layla agreed that the matter was natural, simple, and reasonable, but she questioned whether it would appear that way to her mother or to his. Her mother wanted her to marry as soon as possible, but with a dowry equivalent to what Gamila had gotten, and to a man no less well-off than Gamila’s intended. And his mother? She did not want him to marry now. His mother wanted him to graduate, to open his clinic, to prosper and then to marry the daughter of a pasha or at least a bey. His future was all sketched out in the clearest possible lines and with utter precision, and so was hers. Therefore, her mother would never agree to it, and neither would his. The sisters would work to separate them by all reasonable means and maneuvers, and by less reasonable ones, too. Why should they face this possibility if they did not have to? Why should they make themselves vulnerable to this danger? Yes, she knew that his mother loved her, very much in fact—but on one condition: that Layla not spoil any of her designs, that she not become attached to Isam as he was ascending the ladder, that she not stop him at the apartment of Muhammad Effendi Sulayman before he was able to reach as high as the home of a pasha or bey.

The Open Door

The Open Door